Boomers vs millennials: Who has it better for property?

Nothing divides Australians both young and old like the "who has it harder for property?" debate. Millennials are quick to blame extortionate house prices and stagnant wage growth. Baby boomers hit back with harrowing tales of 17% interest rates and the rampant consumerism of the young.

It's a sentiment as old as time: the younger generation has it easy and the oldies did it tougher. While this is certainly the case with healthcare, technology and the general standard of living, does it ring true for housing affordability as well? Finder decided to dig through the data and end the debate once and for all.

Using a variety of sources (including ABS, RBA, CoreLogic and Finder data), we created a detailed snapshot of the cost of buying a home in 1985 compared to now.

So, who really has it harder?

Interest rates

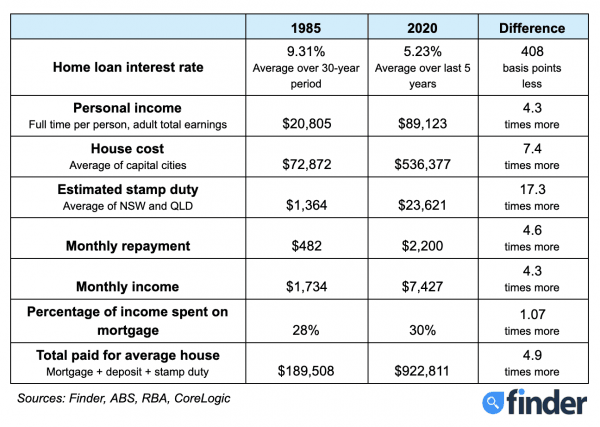

Back in the day, baby boomers forked out huge amounts of interest on their first home. If you bought a house in 1985 and paid it off over 30 years, the average interest rate on a variable home loan was an eye-watering 9.31%1. Fast-forward to 2020 and the average variable rate has dropped to 5.23%2– a difference of 408 basis points. Keep in mind that this is the average advertised rate – many homeowners are actually paying less than this through discounts. With the cash rate also at a historic low of 0.10%, mortgage rates are even dipping below 2.00% for the first time.

But although the older generation paid a higher interest rate on their mortgage, they were also profiting from bigger returns on their savings. The average term deposit interest rate in 1985 was around 12% (read it and weep millennials). These days, term deposits offer a paltry 0.35% on average.

1 Average over a 30-year period

2 Average over the past 5 years

Personal income

Wage growth increased by just 0.1% in the September 2020 quarter, mostly owing to the combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and recession. But millennials are still earning more than their boomer counterparts were. The average annual salary in 1985 was $20,805 – slim pickings when you consider the average annual pay packet is now $89,123. This means millennials are earning 4.3 times more than baby boomers were in 1985.

"But what about the cost of living?" you might ask. Good point – while this has tripled since 1985, the average income has increased by 4.3 times, meaning general living is more affordable than it was in 1985. For example, according to the RBA's inflation calculator, $20,805 in 1985 would be worth around $61,062 today, meaning modern wage-earners are 45% better off. Sorry millennials!

Cost of a property

"Millennials are earning four times more than I did at their age. If they scrapped their holidays and cafe breakfasts they'd be able to purchase a home too," argue the older generations.

Potentially, but property prices have long-since eclipsed wage growth. In 1985, the price of a standard home in a capital city was approximately $72,872 – around 3.5 times higher than the average annual wage. Although house prices have fallen in recent months, the average cost of a home in the capital cities has sky-rocketed to $536,377. This is more than 6 times higher than the average annual income ($89,123) and 7.3 times more expensive than the cost of a home in 1985.

This means that as a young baby boomer, buying a home was more affordable as a proportion of income. In 1985, if the average person saved 80% of their salary, it would take them 11 months to afford a 20% deposit on a property. These days, it would take 20 months to save for a 20% deposit if you saved that same proportion of your income.

Stamp duty costs

Think stamp duty is depressing? Try being a millennial. In 1985, newly minted home owners would have paid around $1,364 in stamp duty costs on average. These days, you're likely to be slapped with a fee of $23,621 – 17.3 times higher than it was in 1985, despite the average house value increasing just 7.4 times in comparison.

But millennials have a useful card up their sleeve thanks to the government's first home owner assistance packages. While these differ slightly between the states and territories, the premise remains the same: eligible first home buyers can apply for a $10,000 government grant to put towards their house deposit, or a full or partial exemption from stamp duty. This can significantly reduce the overall cost of purchasing a home in 2020, whereas boomers had to fend for themselves.

Monthly repayments

If you owned a home in a capital city in 1985, your mortgage payments would have set you back around $482 per month on average. But In 2020, this has escalated to a cool $2,200. This means millennials are spending around 4.6 times more than baby boomers did on their mortgage repayments back in the day.

"But this is all relative to your monthly salary. Young people earn a lot more than the older generations did," one might argue. Not necessarily. The average monthly salary for a baby boomer in 1985 was $1,734. This means they spent around 28% of their income on their mortgage (assuming they had one). These days, the average monthly salary has increased to $7,427, but homeowners will need to spend around 30% of their income on mortgage repayments.

Total paid for the average house

For the price of a standard capital city property, a 20% deposit and stamp duty in 1985, baby boomers could expect to pay $189,508 in total. If they were to purchase a home in 1985, at today's current interest rate of 5.23%, they'd be paying around 1.7 times more than the property's overall value.

As for millennials in 2020? They'll need to fork out a whopping $1,103,596 for the same thing. This means younger Aussies are paying 4.9 times more for a home overall than baby boomers did, despite earning just 4.3 times more. If millennials were to purchase a home in 2020, with the average 1985 interest rate of 9.31%, they'd be paying around 2.6 times more than the property's overall value.

The verdict

According to the numbers, it's millennials who are losing out the most when it comes to property affordability, despite record low mortgage interest rates and a recent dip in house prices.

In 1985, low property prices and high interest rates made saving for a house deposit far quicker and easier than it is today. Interest rates in the late 1980s didn't stay high for long either. This means baby boomers got to benefit from a drop in home loan interest rates over the following years, along with a spectacular rise in property prices.

Average income growth is also forecast to be at its weakest point in 60 years over the next decade. This means paying off the mega mortgage of today is going to be more difficult amid increasing levels of household debt and minimal savings rates.

So, next time the boomer versus millennial housing debate rears its ugly head at the dinner table, young people can rest assured that, according to these figures, the oldies did in fact have it easier. Now pass us the avocado.

Sources

Ready to buy a property? Compare interest rates on a range of home loans now

Ask a question